For What It’s Worth: Points and motivation

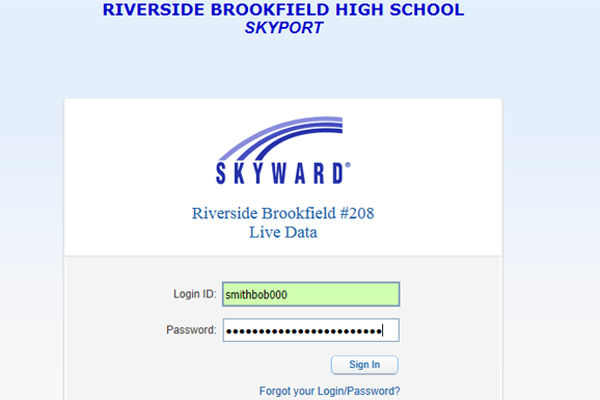

How do our GPA’s, recorded by Skyward, affect our motivation to get things done? Let’s look at some economics to find out!

October 31, 2013

Welcome, one and all!

Today’s topic is, as you might have guessed, points. Specifically, the points that are awarded or denied to students, which make up the basis for a grade in a class. That test was 100 points, say, or that quiz was 27,000. Hopefully it wasn’t.

But, if you had a quiz that actually was 27,000 points, you’d probably study pretty darn hard, right? If you messed up, it could be a huge impact on your grade. The cost of failing would be way more than the cost of studying for a few hours or more, and the benefit would be greater.

Fair enough- points are an incentive system designed to get students to do their work. They’re kind of like Bulldog Bucks in that way, except they come with negative consequences if you don’t do well.

But is the point system actually a good motivator for learning?

Well it obviously isn’t foolproof, or else every student in the school would be doing their homework, studying for tests, and doing their very best to up that point total and thus their grade. We all know that isn’t true. Of course some classes are just flat out difficult, and try as you might, that grade might never make it above a C, or something along those lines. But some people look at a letter grade or a random number and think: what is this? Why should I be running myself ragged for some letters and numbers when I could be doing [insert activity that is important to them]?!?

Regardless of what that other activity is, it’s pretty obvious that the benefits to that person of studying do not outweigh the costs of doing something else. So in that sense, the point system doesn’t work for everyone.

What about the people who do get good grades? Does the point system work for them?

Well, maybe.

They are getting good grades, but does that necessarily mean that they’re learning things? Or are they just memorizing, and getting the bare bones needed to pass a test? If they are more worried about their scores than about the material, that’s probably what’s going to happen. Conider this: how much do you remember from your classes last year? Are there some things you have no recollection of at all, even though you passed the class? Then you were most likely just learning for the test.

So what good did the point system do there?

Assigning different point values to different assignments might also help, or wreak havoc with, students’ ability to prioritize. Everyone knows that you have to prioritize if you want to get things done. That’s pretty much the whole point behind our executive functioning planners.

When you have different assignments due, all worth different point totals, it’s fairly easy to say “I need to study for my 100 point Geometry test more than I need to do this five point Spanish assignment.” Yay! Prioritizing!

But what about things that don’t have point values? Clubs and sports, chores and personal projects, friends and family? How do you fit those into the rigid, demanding point system? From an economic perspective, you’ve got explicit costs for not doing your homework: an F on Skyward. But what are your explicit costs of not walking your dog, or of not drawing that picture you were suddenly inspired to create, or of ditching a club to study for a test? These aren’t explicit, numerical, one-to-one costs. They’re implicit costs. They’re hidden. And if you’re only thinking of the explicit costs, you may lose out.

This is not to say don’t do your homework. School is important. The point is, you really need to understand what the costs are. Sometimes there are more important things than the grades.

The other thing, priority-wise, that the point system might mess with, is classes you enjoy. Ideally, it would be nice to study what you want as in-depth as you like, but unfortunately this system isn’t set up for that. You might end up studying more for classes you don’t like, just to get the grade, while the classes you understand and enjoy go under the figurative bus. If you know exactly what you need to do to get the points, and work is piling up behind you faster than you can blink, you’re less likely to go above and beyond, even if you might have enjoyed it.

You might also be tempted to copy someone else’s homework, or cheat on a test, if the pressure for a higher point total is great enough.

So what, exactly, does this accomplish? We may be learning in school, and we may be completing assignments, but for a lot of people it’s just with a “get it done” mentality, purely grade driven. While such a system has its benefits, the implicit costs, what we give up when we spend five hours studying for a test, aren’t even considered.

What do you think?

This random econ analysis has been brought to you by Kate. Thank you and have a good day.

Scott Duda • Nov 1, 2013 at 6:01 pm

The joys of `Merica and our broken school school system, hooray.