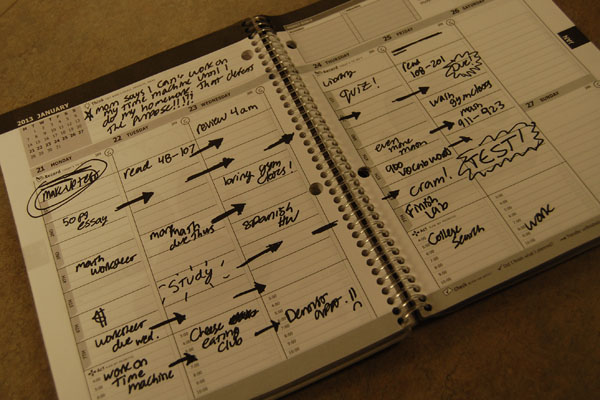

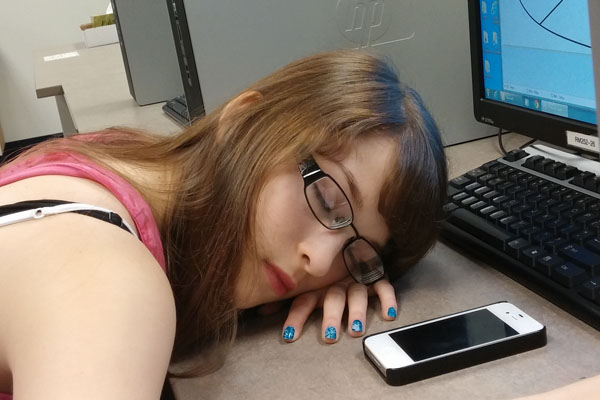

I ought to have finished this column a week ago, but it kept getting put off. I have barely glanced at my AP lit review book, and the test is in a week. I’m rushing to get a grant application in by the deadline. In other words, I’m a procrastinator.

I can feel better, though, because I’m sure you are too.

As it turns out, though, economics can explain why you procrastinate! (It can’t, unfortunately, ensure that you’ll get everything done on time!) However, due to poor time management skills, the explanation will have to wait until tomorrow.

Tomorrow here. We’ll start off with a brief review of Marginal Benefit and Marginal Cost, last seen in The Economics of School Lunch Lines, but used to different effect here. Marginal benefit (MB) is all the extra good stuff you get from each extra minute you spend on something; Marginal cost (MC) is the reverse. When MB is greater than MC, it’s worth it to spend the time that way since you’re getting more than its costing you. When MC is greater, it’s not an efficient use of your time. When they’re equal, that’s where you want to stop. What you put in is exactly what you get out.

Now, let’s apply this to some real-life procrastination.

Homework first. Think about all the factors you unconsciously consider when you contemplate your assignments. There’s how long it will take, how hard it is, how interesting it is, when it’s due, and how big an impact it will have on your grade in the given class. Depending on the answers, each facet will contribute either to the MB or MC of doing the homework.

I’ll now make up a ludicrous example. Suppose you’ve got to write one three-word sentence about anything at all for English. Already it’s looking worthwhile. It’s THREE WORDS, so it won’t take up much time. It may not be interesting, but it’s not tedious. Suppose it’s due tomorrow, and it’s worth 1,000 points toward your final grade. Marginal Benefit is way higher than Marginal Cost there. You’ll probably spend the minute and a half maximum on that homework assignment.

Now suppose on the same night you have to do 5,000 addition problems for Math. That will take a very long time, although it hopefully won’t be terribly hard. It certainly won’t be interesting, though. And suppose it’s due tomorrow and is worth exactly .005 points toward your final grade. In that case, it might be worth it to say “Nope!” and do something else with your time.

So that’s how you might choose which homework assignments to do. Seems fairly simple, right?

Here’s where the procrastination part comes in.

What if you have two assignments, like a large chunk of reading with questions AND a math worksheet? They’ll both take comparable amounts of time in this scenario, and are mostly equal in other aspects. The only difference is the reading is due at the end of the week, while the math is due tomorrow. So the MB of doing the reading is less than the MB for doing the math. Then, once you’ve done the math, it seems too late to do the reading, so you put it off. Imagine in this scenario that you prefer math to reading, and it becomes even more obvious.

The next night you still have the reading, but you also have a science worksheet for the following day. So you do the science, and leave the reading. Since there’s never a night with no homework, the reading gets put off more and more until Thursday night when you’re scrambling to get it done.

Or maybe you do little homework at all. Maybe the MB of doing a worksheet is really small compared to the MC of effort, whereas the MB of playing video games/watching TV/being on the computer/reading/writing/going out with friends/whatever teenagers do these days is greater than the perceived MC. It’s certainly easier to watch TV, and much of the time provides more immediate benefit.

But what about non-homework things, like clubs, AP studying, college searching, chores, etc.? Often times these will get put off because you’ll face immediate negative repercussions for not doing your homework. For me, at least, this is the most common problem. The Marginal Cost of not doing my homework is greater than the Marginal Benefit of doing something else (up to a point).

So there is a simple explanation of why procrastination happens. If it sounds suspiciously like a justification for why this column took me so long… well it might possibly be one. But that said, can Econ be helpful in decreasing your amount of procrastination?

Well, sometimes the problem lies in not accurately judging the MB and MC, because it’s simply easier to turn on the TV and have done with it. Perhaps a moment’s consideration will work some of the time. Perhaps, instead of going for the extremes, you’ll find the place where MB equals MC. Or maybe not.

Another thing that might assist you is forcibly altering the MB/MC scale. If you add additional benefits or costs onto your homework, you might be able to force new behaviors on yourself! Or maybe not. (I am well aware that this is, in most situations, lame advice. But it’s worth a shot if you haven’t tried it yet!).

Well, this column has gone on long enough. Time to get back to AP US history homework. Good luck, procrastinators out there!