In Papers, Please, you play as a border official in the fictional communist nation of Arstotzka, and it is your job to allow in those with the correct papers, and turn away those without them. If you’re thinking, “Pfft, I could that in my sleep,” you’re wrong. Primarily because you’re human, and have a soul. At least I hope you do.

The game starts easily enough, with the single order being “Turn away all foreigners.” It doesn’t stay that way, however, with the restrictions getting stricter and more specific, your family members consistently getting sick and recovering and getting sick again, and the humanity of it all rearing its ugly head. You wield a lot of power, including that of life and death at times, and Papers, Please, makes it very, very hard to wield it in a way that won’t keep you up at night. A large part of why this is is Papers, Please‘s absolutely fantastic writing. The characters, even though they are not human, immediately feel human and filled with personality, making the seemingly simple choice of “Approve or Deny” that much harder. From a border guard pleading with you to let his girlfriend through, to the potential separation of a husband and wife, it is often the smallest plot lines in the game that are it’s most heart wrenching.

Over the game’s one-month long story mode, you are forced to make some tough decisions. You have a family to take care of, a conscience to satisfy, and money to make. Each penalty costs you money, money you could have turned into medicine for your family. Or food and heat. But there’s a woman being chased across the border by someone who she says will kill her. If you let her in, a citation will pop up, and you lose five precious credits, yet your conscience remains clean until the next person in search of a better life walks in. A guard is giving a cut of his detainment bonus, so do you detain innocents, or let them go? Do you nurture the fires of hope, or destroy them, using the justification that you were “following orders”?

There are 20 different endings to the game, some far more satisfying than others, and a timeline-based save system that makes chasing some of the endings easy. However, the game play soon becomes rather repetitive, making the continued pursuit undesirable, unless you get one of the less satisfying endings. While the game play may be repetitive, it is in no way boring or uninteresting, instead always engrossing, from the satisfaction of seeing someone walk out the door and not hearing the overly annoying click-click-click of a citation, to the frustration of getting a citation after the next person because you got their height wrong.

After obtaining one of the 20 endings, or by Googling the code, you unlock Endless mode. Endless mode is split into three sections: Perfection, where the first citation ends it; Timed, where you process as many people as you can in 10 minutes; and Endurance. The three modes are worthy additions to the game, yet they feel lesser than the main story because they lack the human component. The people who walk through your door are just ones and zeroes, empty shells with no meaning, and no true consequences besides an inevitable game over screen.

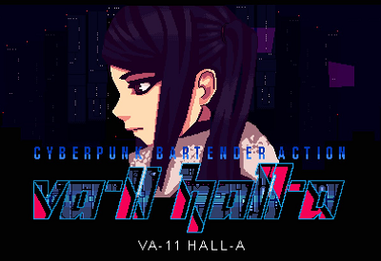

My gripes with the game are few. The limited color spectrum used makes the game very straining on the eyes, and the height scale is a little too well hidden, leading to some cheap citations. Booth upgrades are available, but they are generally useless, just being a button press to perform an action in lieu of a mouse click (with the exception of one, plot important upgrade).

All of it contributes to an extremely oppressive atmosphere, from the 16-bit graphics, the haunting, memorable industrial dirge of a main theme, the limited color palette, the frustration and ever-looming threat of failure, and the immense satisfaction of success, it all fits. Lucas Pope, the sole developer of Papers, Please, set out to create a game under a singular vision. He succeeded in a spectacular fashion, creating one of the best examples of emotional, truly gripping storytelling in video games in the process.

In addition, Papers, Please has managed to make paperwork and banality interesting. That in itself is an accomplishment.